Marie Passey, 12 November 2021

Our second meeting in the Athenaeum Library was addressed by Marie Passey, who was at pains to tell us that she isn’t a historian, but a tour guide. This didn’t prepare us for the scale of knowledge she revealed to us, much of it based on careful and detailed research!

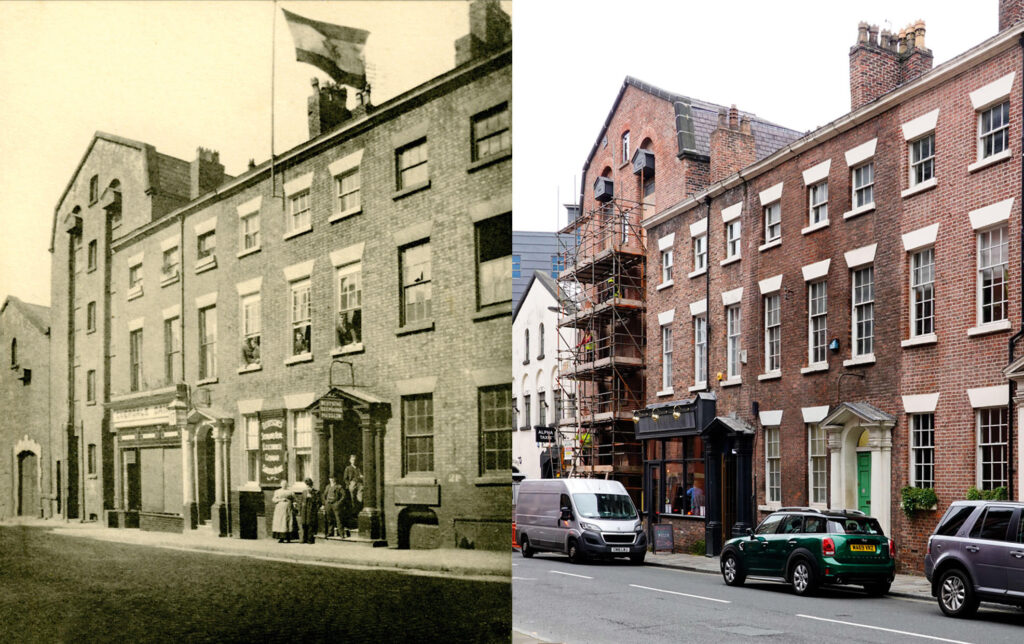

Duke Street is named after the Duke of Cumberland, a royal Duke, known as “Butcher Cumberland”, from the terrible Battle of Culloden. Marie’s verbal and pictorial tour began at the Hanover St end of the street, but first a few general comments on the early years: it was laid out in the 1720s, as a street with residential and business premises. Ropes for the local ships were made in the streets that cross Duke Street – the Rope Walks. It was a prestigious place to live: “in the 18th century,” someone wrote, “the merchants lived in Duke St, above their businesses: in the 19th century they lived beyond their means in the Wirral.”

The street rises gently towards China Town, so that the walker at a brisk pace isn’t out of breath as he or she traverses the street. At the lower end there are several striking round buildings, best among them, perhaps, a redbrick building now divided into flats: in fact, the intersection of Duke St and Hanover St is surrounded by circular buildings, the latest of them, of course, that of John Lewis.

Starting up Duke St from this point, on the left there is still an 1860s warehouse, Wilson’s Buildings, waiting for improvement – quite a fine building in its way. The main change to the buildings has been the restoration of a number of decayed Georgian buildings, as private homes or apartment hotels, and the replacement of decayed buildings with modern hotels, student accommodation and restaurants. A thriving business goes on in the restaurants, many of them of excellent quality. The old Ayrton, Saunders Laboratories have become the Saunders Building, and a few doors up from it, still on the right side of the street, is the Mayflower Restaurant, long-established. And still on the right, after a fine Georgian house now with the self-explanatory name, “Down the Hatch”, is a “gentlemen’s club” called, tellingly “Rude”, in a fine, ostentatious, Victorian house, number 66, that has the look of a bank.

Almost half way up the street, on the left side, there is an impressive town house, next door to a currently unoccupied building at the junction with Suffolk St, which was the Central Library of Liverpool from 1852 to 1860. It retains a grey grandeur, having been designed by John Foster, Senior, a noted Liverpool architect of the period. Across this intersection, there’s a pub from 1817, the Monro, now a gastropub. And in the upper section of Duke St, opposite the junction with Kent St, a lady called Mary Blodget ran a guest house. She doesn’t sound remarkable until you reflect on some of her (likely) customers – Nathaniel Hawthorne, (the American author of The Scarlet Letter) and William Brown, after whom a famous Liverpool street is named. There’s still a Mrs Blodget’s guest house! At 118 lived the famous writer, Felicia Brown, aka Mrs Hemans, better-remembered in the USA than the UK, though most English school pupils at one time knew her immortal line, “The boy stood on the burning deck.”

A British anti-celebrity, John Bellingham, also lived in Duke Street. He is more famous for what he did in London, as he assassinated Spencer Perceval, the only Prime Minister to die in this way, shooting him dead in the lobby of the House of Commons in 1812. Bellingham’s house has gone, and the assassin himself was quickly tried, found guilty, and hanged. (Perceval’s successor in office was the Earl of Liverpool). Further violence occurred in the case of Colonel John Bolton, a Tory politician, who was challenged to a duel by Edward Brooks in 1804. The police got wind of this illegal act, but the venue was switched, and the Colonel killed his challenger by shooting him in one eye.

After all this unpleasantness, it was a relief to hear of a lambana that bears the warning sign, “Please do not feed the animal.” (All tourists being known to be stupid, this is, of course, necessary). Elsewhere, a version of the story of Van Gogh plays with the facts amusingly – go and have a look at it! It really is worth the walk.

A local philanthropist, W. Bridson, (perhaps the ironmonger at 48 Bold St in 1873), who also manufactured weighing scales, built some back-to-back houses for his employees, which survived to be the last such houses in Liverpool: these have recently been refurbished and converted from the original eighteen to nine, by removing the internal shared backs. Our guide got inside one, just before their enhancement, where she found the original cast iron range still in use. The renovated and combined houses are off Duke St to the left, behind Dukes and Duchesses, a nursery, not far from the junction with Berry Street. At this point you should probably cross to the right side of Duke St, to see the Arch, student accommodation, partly in a square behind the facades in Duke St and Great George St./Nelson St. The latter is dated, at its top, to 1887 – a distinguished, all-white front. And near the junction with Nelson St is a business called the Quirky Quarter, advertising “oddball exhibits and optical illusions.” Our guide suggested it is worth a visit, and quite an unusual attraction, with shape-shifting illusions for the visitor.

At the top of Duke St, on the right as you reach this point, is Liverpool’s venerable China Town, with the largest Chinese arch outside China itself. Next to it is the Congregational Church, an impressive structure, accommodating over two thousand people, but now converted to a community centre. Its magnificent pillars were hewn from stone in a convenient quarry in Toxteth.

John Cowell

Nice to read of this from far-away Nova Scotia! I recall vividly the Bridsons buildings as a lunch time hide- away from the Lpool Institute where the Inny boys ate greasy chips and puffed on the occasional Woodbine. Later it featured in what may be the first modern guide ‘book’ which I did for Spiegl’s Lpool Packets. Don’t know if that is still obtainable but it served as my reintroduction to Lpool when I came back to commence my PhD dissertation work ‘Black Spot on the Mersey’ (1976).

Regards and thanks.

Iain Taylor

I enjoyed reading this and attempting to see all the buildings mentioned via Google Maps! I left Liverpool a long time ago, and have only been back occasionally. The differences between then and now is astounding. I got a little lost at the mention of a lambana, which I had to look up and have no idea how that relates to the area;-)

Next time I’m in Liverpool I hope to ‘do’ this tour for real. Thank you!

No.23 Duke Street was a Chinese lodging house in the early 1900’s. My grandfather, who was a seaman, stayed there during the First World War.