Author: Adrian Allen

Publisher: Liverpool University Press 2022

Paperback. 224 pages, over 100 photographs, maps, illustrations etc.

Size 240mm x 170mm

Price: £19.99 (LHS members 30% off with code ALLAN30)

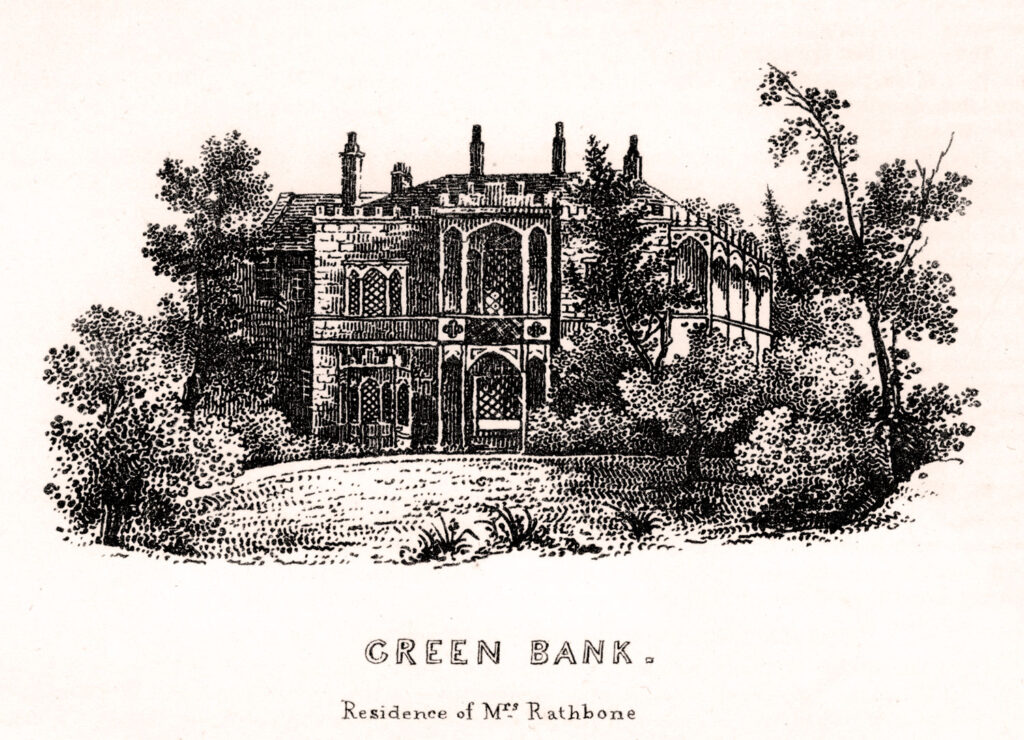

This is a book of two halves. The first part, the most interesting, deals with the history of Greenbank between 1788 and the end of the Second World War. ‘Green Bank’ or ‘Saint Anslow’, as it was known in the 18th century was a modest building, set in some 24 acres, owned by the Molyneux family, and then leased to William Rathbone in 1788. At that time the Rathbone’s main home was at Cornhill, later absorbed into the Albert Dock development. Greenbank was meant to serve as a summertime country residence away from the grime and bustle of the town centre.

Just as interesting as the physical changes made to Greenbank during the 19th century, are the accounts of the various members of the Rathbone family (many of whom were named William: confusing, I know, as there were ten of them!) and their house guests. Within days of landing in Liverpool on 21st July 1826, the famous American bird painter John James Audubon, had been taken under the wing of the Rathbones. Noted for their hospitality to visitors to the town, they later insisted that Audubon quit his Dale Street hotel and move to Greenbank for the remainder of his stay. William Scoresby Jnr., the whalehunter, arctic explorer and cleric, became a friend of the Rathbones after he moved to Liverpool in 1819. When he suffered a breakdown in his health nearly thirty years later, he was cared for by them at Greenbank.

But all good things eventually come to an end and for the Greenbank Rathbones that coincided with the Second World War, the death of Hugh Reynolds Rathbone in 1940, and the almost immediate requisitioning of Greenbank by the Government who used it as a hostel for the WRNS. They delighted in displaying a photograph of Basil Rathbone and boasting that he had lived at Greenbank. Although, at his father’s insistence, he worked for the Liverpool London & Globe Insurance Company for a year, he had no other association with Greenbank or Liverpool of which I am aware and is remembered to his chagrin not as the fine Shakesperean actor that he was but solely as the Hollywood film star who portrayed Sherlock Holmes in 14 wartime-era films.

The second part of the Greenbank story begins with the generous gifting of the house and grounds to the University of Liverpool by Hugh Rathbone’s three children towards the end of the war. And that marked the beginning of the end for Greenbank (well, nearly). Initially it was converted to temporary hostel accommodation for students. Following the building of three new halls of residence at Greenbank in the 1960s, it was then decided that the old house would be adapted as a social centre for students and a conversion was carried out in 1964 by the much-lauded Dr Quentin Hughes of Seaport fame. That use ended in 1986 and it then briefly became part of the University’s conference facilities.

It soon became apparent through old age and neglect by the University over many years that the old house was really showing its age and, whilst some limited maintenance was carried out, by the end of the 1980s its only use was as offices for the University’s Conference Office. Eventually that came to an end and the building was shuttered. As a regular visitor to the Conference Office throughout those years, I can attest to its dilapidated state: the smell of dry rot in the building was particularly memorable. When William Rathbone X unveiled an English Heritage plaque on the house in 2001, he was happily spared the embarrassment of actually entering the former family home.

In 2011 the University unveiled plans to spend the colossal sum of £600m across its wide-ranging estate; £106m was to be spent on the redevelopment of the Greenbank site, including the restoration of its Grade 2* Greenbank House. What follows in the book is a very detailed account of the work carried out before it was finally completed at the beginning of 2020. Curiously, no figure is given for the cost but work of this scale on a heritage building doesn’t come cheap; it must have cost millions, but how many?

So, what did I like and what didn’t I like about this book? Happily, there is much to like, including over 100 well-chosen photographs, maps, and illustrations, and a very useful Rathbone family tree. Many of these photographs, including the 20s and 30s interior images of rooms lived in by the Rathbones, I had never seen before. As I said earlier, the first part of the book is of most interest to local historians; I felt that the second part was perhaps aimed more at those who were involved in the 21st century restoration of the house. Finally, on a personal note, I found that the author’s use of very long sentences and paragraphs a bit off-putting: 100+ word sentences are not uncommon, even including the book’s opening sentence. But that’s a personal gripe and certainly doesn’t put me off suggesting that this is a book worth adding to your collection.

The book can be ordered online from the publishers at a 30% discount by quoting code ‘ALLAN30’:

https://www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/books/id/55521/

Ron Jones